Reefer Cargo Damage: From Reactive Fixes to Proactive Prevention

| Written by Mark Buzinkay

Damage to refrigerated goods often results from a combination of small deviations – being without power for too long, slight temperature fluctuations, missed checks, or delayed responses. All of these gradually compromise product integrity long before anyone notices. This creates a difficult paradox for terminal operators: by the time damage becomes visible or measurable, the opportunity for prevention has already passed.

This article examines why traditional, inspection-based approaches can no longer keep pace with the growing volume of refrigerated cargo and its increasing sensitivity, and why transparency alone is no longer sufficient. It analyses how refrigerated cargo risks actually arise in terminal operations, where manual processes, infrastructure dependency, and time pressures intersect. Above all, it describes the shift from reactive measures to proactive prevention – where continuous data, intelligent alerts, and system-supported safeguards transform refrigerated cargo handling from a fragile process into a controlled, secure operation.

No video selected

Select a video type in the sidebar.

Table of contents:

- Reefer Cargo Damage: A Known, Persistent Risk

- Where Does Reefer Cargo Damage Really Start?

- From Monitoring to Prevention: The Shift in Reefer Thinking

- The Core Technologies Behind Modern Reefer Damage Prevention

- How Does Continuous Reefer Monitoring Work in Practice?

- Data, Evidence, and Claims Defence

- FAQs

- Takeaway

- Glossary

Reefer Cargo Damage: A Known, Persistent Risk

Every terminal manager is familiar with damage to refrigerated freight. The causes are well-known, and the consequences even more so. Yet, despite decades of experience, investment, and optimised procedures, damage to reefer container cargo remains a persistent and costly reality in terminal operations.

Frustratingly, damage is rarely attributable to dramatic failures. More often, it stems from unspectacular but impactful temperature deviations, poor monitoring and maintenance, and mechanical failure of the reefer (1). By the time the problem becomes visible, it's too late. And then it gets expensive; reefer cargo is often very costly. Britannia P&I Club (2) cites the following examples:

- Unintentional thawing of 12 containers of tuna: USD 500,000

- Temperature abuse of 27 containers of fruit: USD 335,000

- Temperature abuse of 3 containers of frozen shrimp: USD 228,000

And that's just the value of the goods. For terminals, the risk extends far beyond that amount. Damage claims are time-consuming and resource-intensive, and can also strain relationships with shipping companies. In a competitive market, this often hurts more than the value of the goods themselves.Damage to refrigerated goods is often considered inevitable: The pressure during peak season, a lack of trained personnel, or outdated infrastructure are cited as inherent risk factors. And while these factors are certainly real, they are not without their limitations.

There is currently no end in sight to the growth in reefer logistics, and therefore, hesitation in finding solutions is unwarranted. Like any strategic risk, the reliable handling of reefers requires constant attention, swift action, and robust evidence.

Where Does Reefer Cargo Damage Really Start?

The time of damage discovery often doesn't coincide with the time of its occurrence. A temperature deviation reported at the distribution centre. A shipment rejected at the recipient's cold storage facility. A damage report received weeks after leaving the terminal. These moments are visible, measurable, and documented. However, in most cases, they are far removed from the origin of the problem.

Special care must be taken at the terminal because this environment is where reefers are most exposed to frequent handling, infrastructure dependency, and operational complexity. Coupling and uncoupling, shunting, vessel operation, maintenance, and shift changes—all of this happens within a relatively short period. Each of these interactions carries a small but cumulative risk.

Terminal operations rely on employees making thousands of correct decisions under time pressure, often at night, in adverse weather conditions, or during peak traffic hours. Errors in stowing reefers, missed checks, delayed reactions, and unintentional changes to target values are not signs of incompetence, but rather predictable consequences of complex systems based on manual processes. The more reefers are handled, the less room there is for error.

raditional manual checks, even when performed carefully, only provide a snapshot in time. They confirm that the reefer was powered and all values met requirements at the time of inspection. What they don't reveal is what happened in the hours before the check or what might happen shortly afterwards. A reefer that has been without power for 40 minutes overnight may appear perfectly fine at the end of the morning inspection. However, the cargo will have experienced this interruption regardless of whether it is recorded in the logbook.Reefer cargo damage accumulates continuously, not according to inspection intervals. Thus, the cause of the damage is often disputed, as a single data point cannot provide a comprehensive picture of the conditions.

From Monitoring to Prevention: The Shift in Reefer Thinking

With the onset of COVID-19, the number of reefer container claims increased, many of them becoming increasingly complex. Claims handling company Marlinblue reported in 2023 that "reefer-related issues now account for a significant 37% of all cargo claims" (3) in its records.

That is also why in recent years, the use of monitoring technologies in the reefer sector has steadily increased; especially at large terminals, power status displays, remote temperature measurements, and sophisticated alarm procedures are now standard. These tools have undoubtedly improved transparency, providing a continuous overview rather than just snapshots. However, surveillance alone is not the same as prevention.

Monitoring provides information about what is happening—or has already happened. It answers the question of status, not outcome. If monitoring simply means that a screen displays a message indicating that a refrigerated container is disconnected from the network, this is useful, but only if someone is actually present and able to assess the consequences of that disconnection. This chain of events would therefore break as soon as the problem goes unnoticed or the person monitoring cannot correctly assess the risk. Thus, transparency remains passive.

This is where intelligent alerts and alarms come into play. Keeping a constant eye on hundreds, if not thousands, of reefs and their conditions is simply not feasible for humans alone. Alarms, based on predefined target values, indicate where problems exist and where intervention is required. This allows humans to focus on resolving the issues.Warnings go a step further, being issued before a problem even occurs. Here, the target values are more narrowly defined, enabling early warnings. These are particularly useful for sensitive goods like pharmaceuticals, where even the slightest deviations can have devastating consequences. Not only are their temperature ranges very narrow, but exceeding or falling below these values also has significant effects, even after a very short time. While some pharmaceutical products do have a certain degree of leeway, the so-called stability budget, it should not be used unnecessarily and must not be exceeded under any circumstances.

The Core Technologies Behind Modern Reefer Damage Prevention

Modern refrigerated container damage prevention is based on a tightly integrated technology stack focused on power supply reliability, temperature stability, and operational accountability. The key difference from previous monitoring approaches lies in how data is captured at the right time, interpreted contextually, and translated into action.

A central aspect is monitoring the power connection. Instead of relying solely on reported temperature information, modern systems verify whether power is actually present at the outlet. This allows the systems to detect complete power outages, as well as intermittently interrupted connections and unstable supply conditions that might never trigger an alarm. This avoids one of the biggest dangers in traditional refrigerated container management: the assumption that "plugged in" is synonymous with "powered".

Besides the power supply, temperature monitoring is a primary focus. Other parameters are also monitored, such as humidity and CO2 levels. It's important that the focus isn't solely on the raw values, but also on their development over time, because damage to electrical components is cumulative and not sudden.

All events are supported by continuous, time-stamped logging. Power outages, temperature deviations, confirmations, and corrective actions are automatically recorded. This creates a complete operational history for each refrigerated container, enabling both real-time intervention and subsequent analysis. For management, this data forms the basis for incident prevention, regulatory compliance, and performance improvement.

Continuous monitoring throughout the entire transport process is of the highest priority – how else can you find out, for example, whether the stability budget has already been used or exhausted?

How Does Continuous Reefer Monitoring Work in Practice?

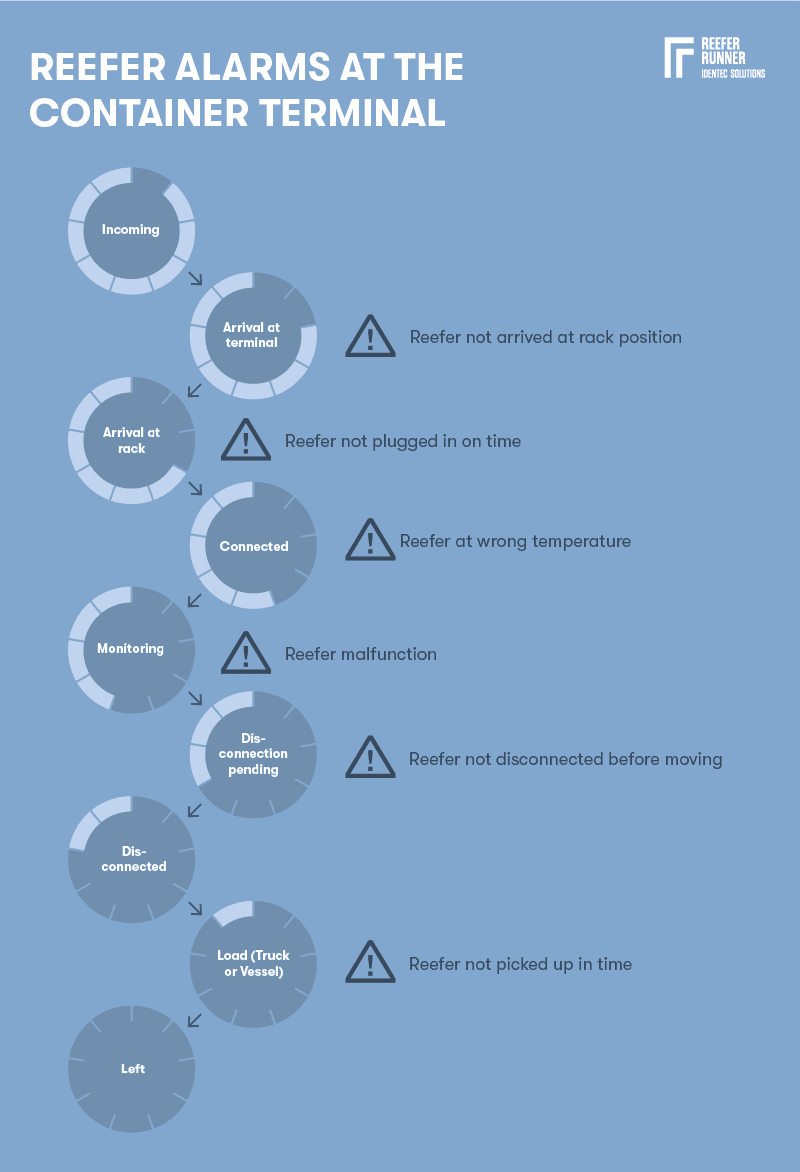

When a reefer arrives at the terminal, is plugged in on time, and all the readings are correct, at first glance, everything looks fine. But what happened during transport up to this point? It may have been en route for days or even weeks.To provide the terminal operator with a clear overview of the journey's history, the reefer unit's trip log can be downloaded. This log shows changes in conditions from the start of the journey, indicating whether everything is running smoothly or if action is required.The reefer monitoring system now takes over at the terminal, monitoring not only the data but also the timeliness of the processes:

- The TOS reports the arrival of the reefer. If it does not arrive at the rack position on time, an alarm is triggered.

- The reefer arrives at the rack position. If it is not connected to the power supply on time, an alarm is triggered.

- The reefer is connected to the monitoring system. If the conditions are not within the specified ranges, an alarm is triggered.

- If power outages, deviations, or reefer malfunctions are detected during monitoring, alarms are triggered.

- When reefers are retrieved from the rack, the process can be defined so that the TOS only issues the working order for moving them once the monitoring system has confirmed that the reefer has been disconnected from the power supply.

- Finally, an alarm is triggered if the reefer is not retrieved on time.

This ensures that the reefer is continuously monitored and its data recorded from its arrival at the terminal until its onward journey by truck, vessel, barge, or train. This is essential for the port's evidence, should any claims arise.

Data, Evidence, and Claims Defence

When refrigerated goods are damaged, the operational challenge is often over once the goods have been partially or completely reloaded, or, in the case of total spoilage, disposed of. However, the economic and legal challenges are only just beginning. Claims are often complex, involve high value, and are frequently disputed. Liability is rarely clear at first glance, and processing times can sometimes extend over weeks or even months. In this context, the quality of the data and evidence available to the terminal often determines not only the outcome of the claim but also the effort and costs required to pursue it.

In the past, claims management relied on a patchwork of information: manual inspection logs, shift reports, alarm logs from individual refrigeration units, and recollections from employees who might no longer be working the same shift or even at the terminal. While this information could demonstrate that procedures were followed, it rarely provided a complete, objective record of the conditions. The result was a defensive stance based on claims rather than evidence.

Monitoring with modern systems fundamentally changes this situation. Instead of having to reconstruct events after the fact, terminals can provide a complete, time-stamped record of power and temperature conditions throughout the container's entire stay. Every interruption, deviation, confirmation, and intervention is automatically logged. This creates a factual account that is difficult to refute, even if claims are made long after the container has left the terminal.One of the greatest advantages is that not only the occurrence of an event, but also its duration and impact can be documented. Many claims depend on whether an event was long enough or severe enough to plausibly cause damage. A brief power outage or a minor temperature deviation might be operationally acceptable, but without precise time data, it can be problematic. Continuous recording allows terminals to accurately demonstrate how long an event lasted, how quickly it was resolved, and whether temperatures ever reached levels known to affect the respective type of charge.

Container terminals are only one link in a longer chain of responsibility; objective data enables them to clearly define their area of responsibility and to demonstrate that the conditions during this period were within acceptable limits.In addition to improving external communication, the data collected by modern monitoring systems also enhances internal coordination between operations, maintenance, sales, and customer service teams. Instead of discussing potential causes, they can interpret the recordings of actual events and prepare an appropriate response.Furthermore, beyond individual incidents, the collection of historical data supports a more strategic approach to risk management. Patterns in loss-related events can be analysed to identify systemic weaknesses—specific infrastructures, processes, or operating conditions that correlate with increased risk. This enables targeted improvements that reduce future loss volumes rather than merely mitigating them.

When terminals can demonstrate robust monitoring and rapid response capabilities, the focus shifts from blame to cooperation. Trust grows, and in some cases, disputes can be resolved before formal claims arise. Continuous monitoring also builds credibility. And in the area of refrigerated goods incidents, it is often an effective safeguard.

FAQ

What Are the Most Common Reefer Cargo Damages?

Many types of refrigerated goods are very sensitive to temperature fluctuations, as well as humidity, air circulation, and sudden environmental changes.

The spoilage of fresh produce is the most common type of damage. If the target temperature is not met or air circulation is uneven, fruits and vegetables can overripen, lose their desired consistency, or develop mould.

Frozen goods such as seafood, meat, and frozen meals can partially thaw and refreeze. This impairs their quality, sometimes rendering them inedible.With pharmaceuticals, deviations can lead to undesirable chemical processes. Even slight deviations can cause vaccines, biologics, and some medications to lose their effectiveness. In specialised fields such as art and antique transport, damage such as warping of paintings or paint flaking can occur. Musical instruments can go out of tune or develop cracks. Sensitive electronics can suffer from condensation, corrosion, or performance degradation if stored under suboptimal conditions.

Even if only the packaging or the appearance of the products is affected - for example, by moisture and condensation - this can render a shipment unsaleable.

Takeaway

Damage to refrigerated goods is not an unavoidable cost in terminal operations, but rather a systemic risk that can be actively managed and significantly reduced. The crucial shift lies in the move towards continuous, preventative monitoring. By monitoring power stability, temperature behaviour, and process flows in real time and converting them into actionable alerts instead of raw data, terminals can intervene before quality is compromised.Equally important are comprehensive, time-stamped records. These change the dynamics of damage handling. Instead of reconstructing events after the fact, terminals can rely on objective evidence to demonstrate compliance, clarify responsibilities, and protect business relationships.In times of steadily increasing refrigerated goods volume and cargo sensitivity, prevention is an operational necessity. Terminals that integrate prevention into their refrigerated goods processes reduce losses, strengthen trust, and turn data into a strategic advantage rather than an after-the-fact explanation.

Delve deeper into one of our core topics: Refrigerated containers

Glossary

A stability budget is the allowable amount of time that a temperature‑sensitive product (e.g., pharmaceuticals, biologics, some vaccines) may spend outside its specified storage conditions (such as 2–8 °C or below −20 °C) without compromising quality, safety, or efficacy. It is calculated from stability studies and expressed as “time out of storage” (TOS), which is then allocated across the supply chain—manufacturing, packaging, distribution, temporary excursions, and end‑user handling—so that the total exposure never exceeds the validated limit. (4)A trip log for a reefer container is the electronic record of all relevant operating and environmental parameters during a transport “trip.” It is typically generated by an integrated data logger and stores time-stamped data such as supply/return air temperature, setpoint changes, defrost cycles, power interruptions, alarms, and sometimes humidity or controlled-atmosphere values. At destination, the trip log is downloaded and reviewed to verify cold-chain integrity, support claims handling, and demonstrate compliance with customer and regulatory requirements. (5)

References

(1) https://www.swedishclub.com/uploads/2023/12/TSC_Container_focus_Reefers_2022_WEB.pdf

(2) https://britanniapandi.com/2022/04/refrigerated-container-cargo-claims/

(3) https://marlinblue.com/reefer-cargo-claims/

(4) Carstensen, Jens T.; Rhodes, Christopher T. (2000). Drug Stability: Principles and Practices. 3rd ed., Marcel Dekker.

(5) Hodges, J., & East, A. (2016). “Temperature Monitoring and Record Keeping in the Cold Chain.” In: Food Cold Chain Management, Woodhead Publishing.

Note: This article was partly created with the assistance of artificial intelligence to support drafting.

Author

Conny Stickler, Marketing Manager Logistics

Constance Stickler holds a master's degree in political science, German language and history. She spent most of her professional career as a project and marketing manager in different industries. Her passion is usability, and she's captivated by the potential of today's digital tools. They seem to unlock endless possibilities, each one more intriguing than the last. Constance writes about automation, sustainability and safety in maritime logistics.